Luis Fernando Camacho, governor of Santa Cruz department and regional leader in 2019 protests against Evo Morales, was arrested on December 28, 2022, as a suspect in the Golpe de Estado I (Coup d’état I) investigation. Camacho, whose public statements suggest that he and his father coordinated with the military and police prior to Evo Morales’ ouster, has been named as a suspect as well as convened to testify in the inquiry. The formal charge against Camacho is “terrorism,” though its specifics are more akin to insurrection against elected authorities. Camacho was sentenced to four months of preventative detention, during which time prosecutors promise to deepen their investigation of the nexus among Camacho’s Civic movement, the incipient Áñez government, police mutineers, and military conspirators in November 2019. (For today, I’m not blogging my thoughts on the legality, strategic wisdom, or ethics of this arrest.)

Camacho’s arrest was widely expected. He was known to be the subject of at least eight criminal investigations. As it turned out, the arrest order had been issued on October 31. Three days before, he had issued a video publicly challenging Justice Minister Iván Lima:

Ministro, usted que encabeza esto, que está buscando incriminarme con casos de violencia, no sea cobarde: si quiere, deténgame, deténgame, venga, deténgame

Molina, Fernando. “Detenido el gobernador boliviano de Santa Cruz, Luis Fernando Camacho, por la crisis que llevó al derrocamiento de Evo Morales.” El País, December 28, 2022.

Minister, it is you who are at the head of this, who are seeking to incriminate me in cases of violence. Don’t be a coward: if you want, detain me, detain me, come here and detain me. [my translation]

Almost immediately, the arrest itself kicked off a new wave of protests in Santa Cruz department, headed by the department‘s civic movement. Camacho previously headed the Comité Cívico Pro-Santa Cruz in 2019 and was Vice President of the Unión Juvenil Cruceñista in 2002–2004. These institutions, joined by the public voice of governor Camacho since his April 2021 election, have engaged in waves of protest challenging the MAS–IPSP governments of Evo Morales (2006-2019) and Luis Arce (2020–). While demands have varied widely—rejection of the constitutional assembly and departmental (2006–08), rejection of judicial elections (2012), of penal code reforms, of alleged electoral fraud (2019), an anti-money laundering law (2020), and a census delay (2021), the mechanisms of regional protests have been relatively stable.

Like other regions, Santa Cruz goes on strike through road blockades and a city-wide work stoppage. And during the 2006-09 political standoff and since 2019, these tactics were enhanced by peaceful or forcible takeovers of national state institutions, as well as direct physical attacks on institutions associated with the governing MAS-IPSP party, such as labor unions and Indigenous organizations, and attacks upon so-called “traitors” to the region, which is to say local MAS-IPSP politicians.

While used only sparsely between 2009 and 2019, arson has been an important tactic for the Santa Cruz Civic movement during the so-called catastrophic stalemate of 2006 to 2009, during the October–November 2019 political crisis, and in protests since Luis Arce’s October 2020 election. (I detail the broader use of arson in the 2019 crisis and the catastrophic stalemate in a forthcoming article in the Bolivia Studies Journal.)

Immediate Responses to Camacho’s Arrest

The first responses by the Civic Movement to their leader‘s arrest were attempts to prevent his transport out of the region. Protesters flooded into the terminals and runways at Viru Viru International Airport and El Trompillo Airport. Per El País (of Madrid):

A group of hundreds of the governor’s sympathizers, led by regional authorities and [parliamentary] deputies, headed to the Viru Viru airport in Santa Cruz. There, they overwhelmed and beat security personnel, invaded the runway, entered some of the airplanes waiting to take off, and obliged the passengers to disembark, to prevent Camacho from being taken from Santa Cruz. They didn’t find him. Despite this, they decided to paralyze the airport after [Camacho’s] detention.

Molina, Fernando. “Detenido el gobernador boliviano de Santa Cruz, Luis Fernando Camacho, por la crisis que llevó al derrocamiento de Evo Morales.” El País, December 28, 2022

Among the elected officials present was Paola Aguirre, who reportedly vowed, “No sale ni un avión de este aeropuerto [Not one plane will leave this airport.” Aguirre posted a 33-minute video to her Facebook page beginning with her atop a boarding staircase to an airplane, including an impromptu press conference on the tarmac, live questioning of the airport director about whether Camacho had boarded a BOA flight (at 15m50), and vows that any damage or inconvenience caused to the airport is the responsibility of the national government who ordered Camacho’s arrest (at 30m50).

Flights from Viru Viru resumed on December 29. Airport officials reported 5,000 travelers were affected, with 350,000 Bs (~ $50,000) in material damages and 900,000 Bs. ($130,000) in accommodations purchased for inconvenienced passengers.

The New Daily Protest Cycle

With Camacho successfully removed from the department, the protest mood turned to rage.

Pro-Civic Movment newspaper El Deber reported a “night of fury” that consumed three buildings: the prosecutor’s office, a drug control office that has been used for negotiations w/ the national government, and the home of Minister of Public Works Edgar Montaño.

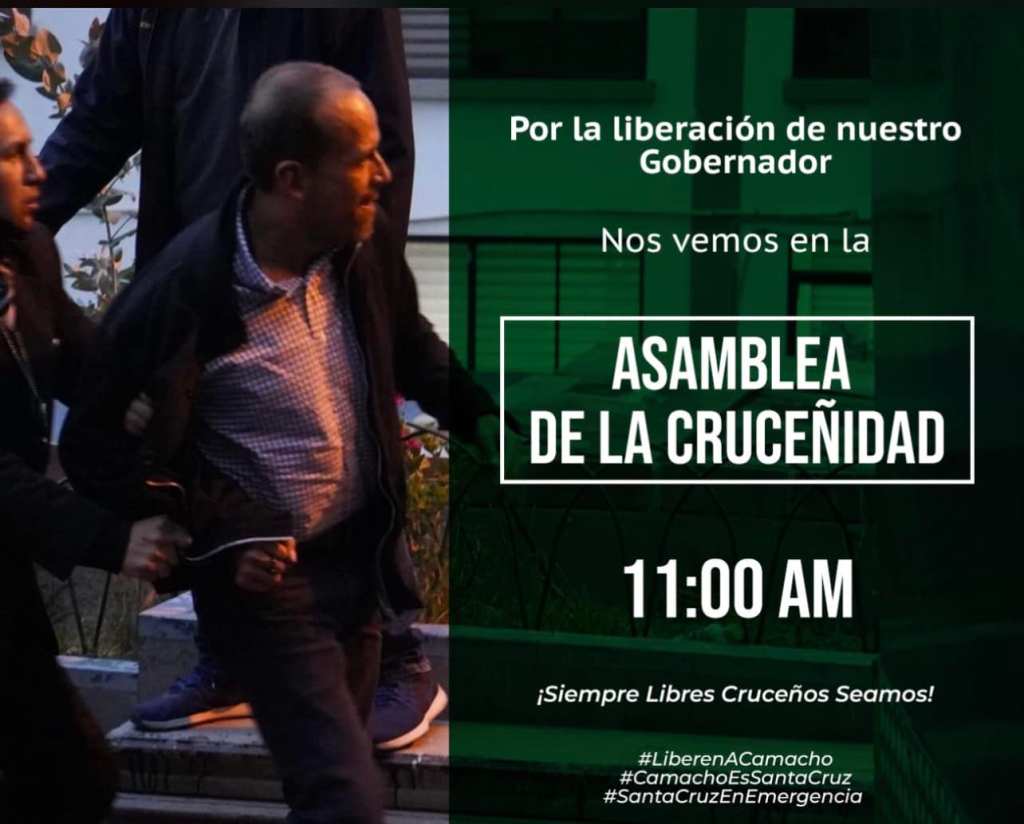

In its public pronouncement, the Cruceño civic movement called for road blockades to begin at midnight (December 28/29) and the takeover of public institutions, both key tactics in past protests, including the 36-day strike in October–November of 2022. It, along with former centrist presidential candidate Carlos Mesa, qualified the arrest as a “kidnapping” and the act of a “dictatorial” national government. It has convened mass gatherings to mount a new regional mobilization until Camacho is freed.

What is apparent after three nights is that this new wave of mobilization has a daily cycle with a daytime phase focused on blockades and calmer occupations held at/in front of national institutions and a nighttime phase of confrontations with police during which protesters attempt to seize and burn the same class of institutions.

Here are daytime actions, as photographed by the Unión Juvenil Cruceñista:

And night-time attacks on the same class of public institutions, sometimes literally the same ones (like the ABT, the Administration of Forests and Lands) pictured in peaceful protests.

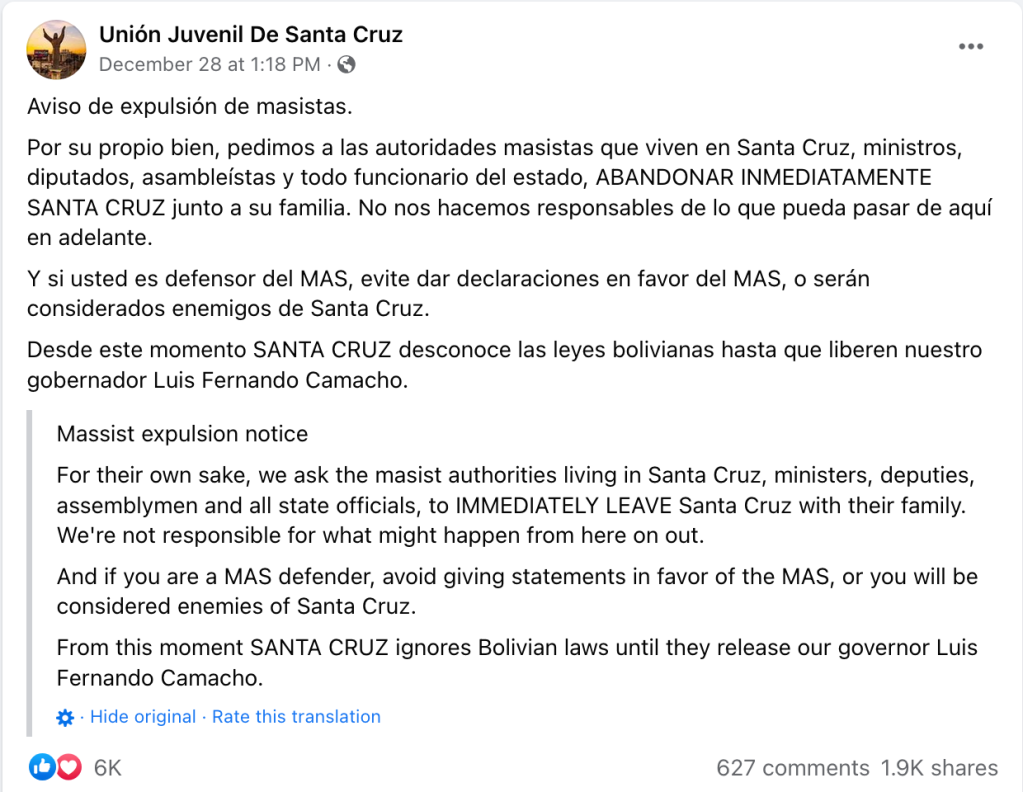

The logic of these actions is twofold: first, a public repudiation of the legitimacy of the national government and second, the assertion that only MASistas work in such instutions and they are “traitors to the region.” A widely shared “order of expulsion” posted by a non-official(?) UJC account urged MAS supporters to leave Santa Cruz. It was “shared” over a thousand times and widely reposted beyond that.

The formal leadership of the Cruceño organizations has been careful to label the arsons as the work of “infiltrators” in their ranks or so-called “self-inflicted attacks” by MAS-led institutions. The claim that a small number of closeted pro-government arsonists are hiding themselves nightly in anti-government crowds who only want to fight the cops is, to say the least, not especially credible. The will and capability of the Santa Cruz civic movement to carry out both crude and sophisticated arson attacks was demonstrated amply in the October 2019 burnings of electoral offices in protest over alleged voter fraud, and numerous attacks during the 2006-09 political crisis.

What is the actual relationship between the daytime pronouncements of the Comité Pro-Sana Cruz and the Unión Juvenil Cruceñista, and the nighttime actions of arson? Is there a real split over tactics, or merely an effort to deny responsibility for arson and insurrection, which might be distasteful to potential foreign allies?

Here’s how Camacho-aligned congressional deputy Paola Aguirre answers that question:

La ciudadanía cruceña, como en su momento lo dijen, no tiene patrones. Ellos se han autoconvocados desde el momento en que se enteraron que el gobernador Camacho estaba siendo secuestrado por el regimen del President Luis Arce. Y han tomado acciones por iniciativa propia. El Comité Cívico Pro-Santa Cruz prácticamente el día de ayer [29 de diciembre] ya la ha dijo a la ciudadanía, ‘ya, tomen ustedes las determinaciones que consideren convenientes.’

Este paro de 24 horas definitivamente es una de las menores medidas que se va tomar. Santa Cruz está convulsionada y no va a volver a la normalidad en cuánto no se restituya la libertad del Gobernador Luis Fernando Camacho. Por que no se trata de encarcelar a Camacho, se trata de encarcelar el voto popular de cientos, miles, y millones de Cruceños que han decido elegir a Camacho como Gobernador.

Paola Aguirre, interview with Radio Fides, 30 December 2022. At 7m30 in video posted on her Facebook page.

Translation: “The Santa Cruz citizenry does not, as is sometimes said, have bosses. They have convened themselves from the moment they knew that Governor Camacho was being kidnapped by the regime of President Luis Arce. And they have taken actions of their own initiative. The Pro-Santa Cruz Civic Committee practically said to the citizenry yesterday, ‘Alright, you take the determinations that you find convenient.’

“This 24-hour strike is definitely one of the smallest measures that will be taken. Santa Cruz has been convulsed and normality will not return so long as the freedom of Governor Luis Fernando Camacho is not restored. Beacuse they are not just trying to imprison Camacho, but they are trying to imprison the popular vote of hundreds, thousands, and millions of Cruceños who have decided to elect Camacho as our Governor.”

What is clear is that, today, the daytime organizations are now mobilizing for the freedom of protesters imprisoned for confrontation and arson.

![A Facebook invite from Unión Juvenil Santa Cruz (not the official account of the UJC), reads, "Gran Bienvenida del 2023 / Recibamos este nuevo año a los pies del cristo / Desde los 22 horas / Entrada: Vinagre, mascara antigas, agua, balde, bicarbonato, palos, piedras, escudos, pinturas, petardos, etc. / Te esperamos!"

"Great Welcome to 2023 / Let's receive this new year at the feet of the Christ [the Redemeer statue] / From 10pm onwards / Entry fee: Vinegar, gas mask, water, bicarbonate, sticks, stones, shields, paint, rockets, etc! We're waiting for you!"](https://woborders.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/screen-shot-2022-12-31-at-3.42.49-pm.png?w=1024)