Five years after his ouster from office, former president Evo Morales is suddenly facing a serious investigation into his apparent sexual relationship with a minor at the height of this presidency in 2015–16. The allegations cover the illegal and coercive nature of the relationship as well as allegations that the girl’s parents traded sexual access to their daughter for political favors from Morales. The fact of Morales’ sexual act appears to be proven by the subsequent birth of a child in February 2016, on whose birth certificate (revised in 2018) Morales’ name appears as father.

However, the underlying charge of estupro (roughly, but not exactly equivalent to statutory rape) cannot be prosecuted without the participation of the alleged victim in the prosecution. The criminal investigation therefore rests on the link between the then-57-year-old president’s coercive sex with a fifteen-year-old and public corruption. Per the prosecutors’ document seeking Evo Morales’ arrest:

The teenager had been enrolled by her parents in the Generation Evo youth group “with the sole purpose of being able to climb politically and obtain lucrative benefits, that is, to get what they wanted in exchange for their minor daughter, among them to obtain privileged positions, economic stability and political benefits, being this in such a way that by convincing, pressure practically forced the teenager to maintain a carnal access with … Evo Morales Ayma”. (“¿Cuáles son los detalles del escándalo en la denuncia contra Evo Morales?”, Opinion, October 3, 2024 )

Prosecutors allege that the parents were repaid with multiple benefits from the Morales administration, including a failed nomination of the victim’s mother to be a regional legislative candidate.

The investigation of the case by Bolivian prosecutors was first prompted by a complaint from the Vice Minister of Transparency Guido Melgar, just three weeks before the end of Jeanine Áñez’s interim government. The recent prosecution concerns the same victim, but with new charges—sex trafficking and corruption—that can be considered without her filing a complaint. Restrained from progressing for years, and challenged by Morales as politically motivated persecution under both the presidencies of Jeanine Áñez and Luis Arce, the case has finally convened the former president to testify on October 10.

And he, in turn, has convened his political allies to resist the prosecution in the streets.

A history of allegations surrounding Morales

These new allegations, as so often is the case in sexual scandals, have a history. In February 2016, Carlos Valverde revealed that Evo Morales had a 2007 affair with Gabriela Zapata, then an 18-year-old lobbyist for a Chinese firm seeking contracts with the government. The affair proved embarrassing for Morales, then seeking a mandate for re-election, but was soon overshadowed by the woman’s evident deceit about having a child with Morales. Zapata was eventually convicted on other influence-trafficking charges, though Morales’ complaint against her for psychological abuse (regarding the alleged child) failed.

Following Morales’ forcible ouster in 2019, the president fled in to exile in Mexico and Argentina. The interim government that followed pursued investigations of his relations with underage girls, eventually arresting Noemi Meneses, who was 19 at the time, and seizing her phone. Prosecutors leaked extensive transcripts of her text messages with Morales dating back several years. A March 2020 profile piece on Morales by John Lee Anderson (among other things, one of Che Guevara’s biographers) described an unnamed young woman in Morales’ entourage-in-exile, suggesting a relationship he wanted kept out of the press.

As we spoke, I became aware that a young woman was listening to us from a chair a dozen feet away. She had straight dark hair in pigtails, and she was dressed in jeans and a black T-shirt, with the word “LOVE” in sparkly white letters. She and Morales occasionally exchanged glances and smiled. At one point, Morales interrupted our conversation to tell my photographer not to take pictures of the woman. Later, as Morales posed for photographs, she asked me to take her portrait using her phone. She stood with her back to the garden wall, giggling playfully at Morales, who was posing a few feet away.

Anderson later identified her as Noemi, writing on Twitter, “Why do you think I mentioned her? Anyone will realize that I included her exactly because her youth caught my attention, although I never knew her age, so I could not affirm that which I didn’t know.”

It was at this time that Guido Melgar first raised the question of a second victim in Yacuiba, the girl about whom Morales is currently expected to testify.

New allegations regarding Morales in exile

This week, a new witness has stepped forward, both confirming that Noemi Meneses was resident with Morales in Argentina, and alleging that the pattern of trading sexual access to children for political favors from Morales continued during 2020.

These explosive allegations come from Angelica Ponce, formerly a national leader of the Confederación Nacional de Mujeres Interculturales de Bolivia, the women’s organization of agrarian colonist communities. Ponce campaigned in 2019 for Evo Morales’ re-election. She took a role in 2021 in the Arce government as head of the Autoridad Plurinacional de la Madre Tierra, an environmental agency. In 2022, Ponce publicly broke with Evo Morales, accusing him of everyday sexism on his return from exile. Her public critiques quickly led to her expulsion from the Intercultural women’s federation.

Speaking to the press on October 14, Ponce recalled her visits as a leader to Evo Morales’ residence-in-exile in Argentina, including with representatives of victims of the Senkata and Sacaba massacres.

It’s important to recognize that Evo Morales, yes, was living with minors in Argentina. I am a witness to that, so I think it’s important to denounce before the international community that a person of this measure is threatening the stability of Bolivia. … He was with Noemi and with three minors. … I went with the injured of Senkata and Sacaba, and he didn’t even want to receive me with the injured people. He would rather still be with the girls, with the minors.

And if we can speak of it—the former organizational leaders, the former officials, those of us who passed through there—Evo publicly said: all of those who needed public works done would give him a girl. And so, no one can stay silent any more. God is going to see us, God is going to judge us, brothers and sisters. This man has been a damaging guy, who has made a very lamentable misdeed to rape girls, and who needs to pay in prison.

I, as a former executive leader, I have seen how Evo Morales would take the girls from events delivering public works. [My translation from Angelica Ponce, entrevista, “‘Estuvo viviendo en su mansión con menores’“]

MAS leadership disavowed Evo’s behavior in 2020

By 2020, the question of Evo Morales’ sexual relations with underage girls became both a matter of criminal investigation and political responsibility for the party, appearing in multiple statements by MAS leaders, including future vice president David Choquehuanca, who addressed the issue in a September 2020 interview:

With regard to the denunciations against Morales for statutory rape [estupro], he said that, if there is proof, Morales will have to submit to justice and he said he does not know how many children the former president had during his government.

“I think that he [Evo Morales] has more than the two [children he publicly recognizes], it is possible that he has not recognized them. … I don’t know how many women he will have had [during his term].I cannot say ‘so many women’, but that there have been some. I have said there there is machismo, and that we have to struggle against it.” said [Choquehuanca] in an interview with Radio Deseo. (https://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/pais/20200925/futuro-evo-exministros-ponen-aprietos-arce-choquehuanca.)

Likewise, Chamber of Deputies President Sergio Choque Siñani speaking shortly after Luis Arce’s election victory said, “Perhaps [Evo Morales] will return to the country, but he will have to return to take on his own defense with respect to the legal charges that have been openened against him by this interim government, and also by private individuals. The ex-president will have to come and assume his defense, and well defend himself, right, in accordance with what the constitution asks.” “Tal vez retorne al país, pero él tiene que retornar a asumir defensa respeto a los proceso proceso que han aperturado — esta gestión transitoria, denuncias también de personas. Todo ello el expresidente tendrá que venir a asumir defensa, y bueno defenderse, no, de acuerdo al que reza también la constitución.“

These statements were part of a broader effort by the MAS-IPSP leaders to turn the page on Evo Morales, both to win the election and to establish a “MAS 2.0” government with its own identity. These efforts would be complicated, however, by Morales’ national and global celebrity status and by his continuing position as leader of the party during the course of the election. Ultimately this led to a formal break in 2023, with Morales and Arce leading two different organizations each claiming to be the rightful Movement Towards Socialism party.

Criminal investigation intersects with Morales’ renewed effort to run for president

Now, with less than a year until the next presidential election (on August 17, 2025), Evo Morales’ faction is pressing for both the MAS-IPSP ballot line and for an end to the charges against Morales, which it terms “judicial persecution.” On both these matters, the ex-president finds himself at odds with the current Arce government, as well as the theoretically independent judicial and electoral branches. The Supreme Electoral Tribunal de-recognized Morales’ faction in October and November 2023. Morales was ruled ineligible to run for the presidency by the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal in December 2023. The Evista faction faced off with the government in a January 2024 blockade campaign that focused on judicial elections.

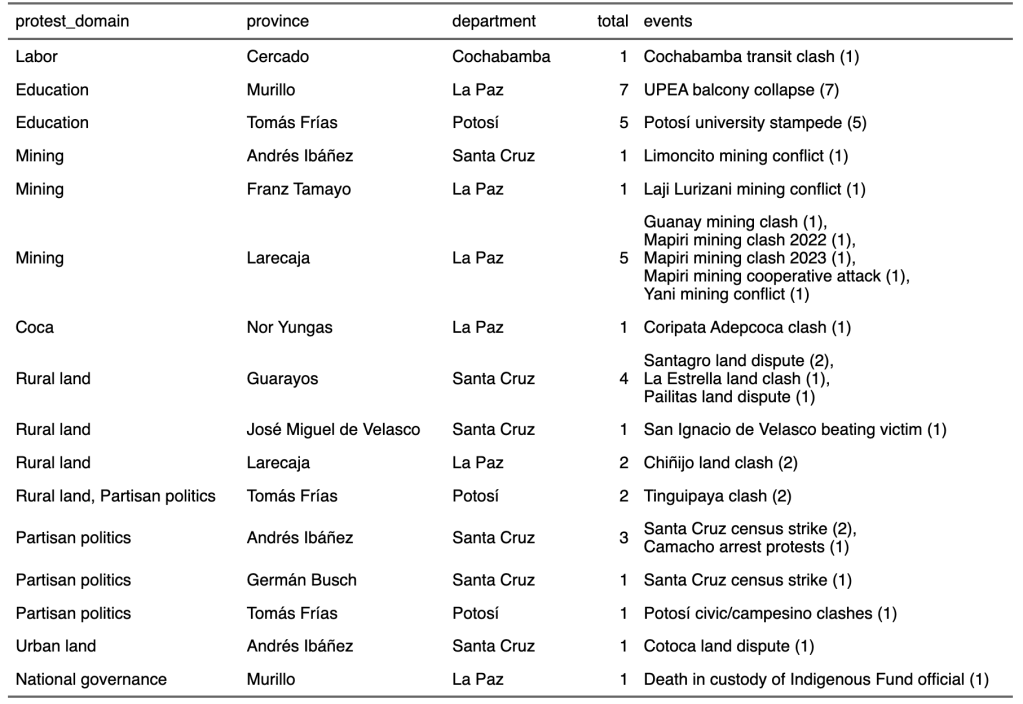

Evo’s threatened arrest for failing to testify on October 10 has now been rolled in to his faction’s latest round of mobilization. Backed by factions of the coca growers, intercultural, and peasant unions, these blockades began Monday, October 14 in three points in Cochabamba, with a threat to escalated to nationwide road blockades by the following Monday. Blockaders put forward ten demands: four calling for the roll back of Supreme Decrees issued by President Arce, one calling for a 44-km highway project, one related to fuel supply and prices of goods, two opposing judicial persecution of Evo Morales and his allies, and one demanding his presidential candidacy be recognized.

By the weekend, the blockades had expanded across Cochabamba department and reached isolated locations in Santa Cruz and La Paz. They have isolated Cochabamba from other cities and begun to impact the fuel supply in La Paz and El Alto. But they were limited in scope and number (reaching no more than 24 sites) compared to past mobilizations on behalf of the party, reflecting the concentration of Morales’ base in eastern rural Cochabamba.

It remains to be seen how many rural farmers are willing to mobilize in defense of Evo Morales’ political future, how seriously this mobilization will advance other demands, and how many voters will emerge alienated or disgusted by the charges weighing against the ex-president.

Lead image: Members of the Generación Evo youth organization march in Yacuiba in support of his 2025 candidacy. Evo is alleged to have used Generación Evo coercively as a source of underage sexual partners.