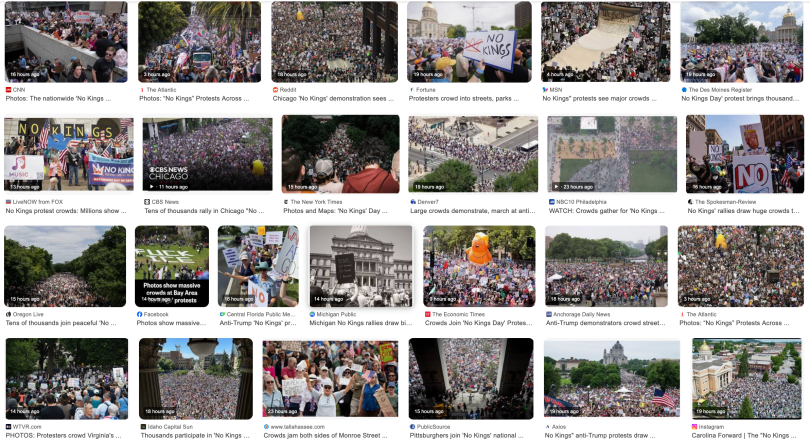

Americans, citizens and immigrants alike, protested on Saturday, June 14, in exceptional numbers as a wave of No Kings protests became the most widespread public repudiation of the second Donald Trump administration. These protests, which were undoubtedly energized by the standoff between Los Angeles-area communities and Federal troops, could mark a turning point from isolated protests to mass resistance.

Protests are called demonstrations for a reason. And these were displays of political strength for a movement that has a lot to prove: that it better represents the country than a president elected with a slim plurality in November 2020, that it is better able to capture public enthusiasm than an incipient fascist movement, and that it is undeterred by the state violence shown through military deployments, arrests of opposition leaders, and near-disappearances of a growing number of immigrants.

So what does success look like for a mass display of public will?

One simple metric is comparative: did a the anti-Trump movement out-organize and out-turnout their opponent. And here, the juxtaposition with Trump’s military parade — a celebration of the US Army’s 250th birthday on Trump’s 79th — will be unforgettable.

But in a larger sense, protesters make a political statement through crowds (and yes, through many other kinds of actions, but June 14 was largely a day for crowds). When they succeed, that message is “indisputable in its overwhelmingness,” as Argentina’s Colectivo Situaciones described the protests that brought down three presidents on December 19 and 20, 2001. Through some alchemy of place, time, presence, voice, and action, crowds constitute themselves into the “The Voice of the People.” And assert that they, and not their government, will decide the future.

I want to use this occasion to share how those of us who study mass protest try to conceptualize just how protests achieve that kind of political impact.

Charles Tilly, who with various colleagues has probably done the most to examine the protest demonstration as political form, has a four-word summary of what protesters are actually demonstrating. And Tilly’s model is interesting in part because it situates demonstrations as just one form of collective political action (or “contentious politics”), alongside riots, strikes, revolutions, and among many other attempts at disruption or representation. Demonstrations are a social transaction where movements accept that a government system will persist, but where governments are moved to recalibrate their actions based on shifts in popular support and public mode. In that frame, Tilly et al. argue that protesters are engaged in displays of WUNC: worth, unity, numbers, and commitment.

- Worth: Protesters present themselves as worthy of political participation, rather than exclusion from decisions about their own fate. This might be especially relevant for groups, from working-class laborers in the 19th century to women in the suffrage movements to minorities of various enfranchisement movements, who are formally excluded from participating in official politics. This is self-presentation as an argument that one deserves a place at the table.

- Unity: Protesters come together and present a common voice. This may be the most basic element of what a common protest is, and everything from a speaker’s dais to roars of approval to marching side-by-side demonstrates this unity of purpose, both to participants themselves and to their audience.

- Numbers: The size of a protest illustrates the larger capacity of a movement to catalyze political action, to show up again, and to influence democratic outcomes. When the 2006 immigrant protests promised, “Hoy marchamos, mañana votamos / Today we march, tomorrow we vote,” they were offering their quantitative weight to political actors that would accept their agenda.

- Commitment: To a greater or lesser degree, protests demonstrate the willingness of participants to do hard things, to devote a share of their time to political action, and to make sacrifices for a cause. This is why long marches, gatherings in spite of rain or cold, and endurance of repressive violence—fire hoses, dogs, tear gas, projectile weapons—are so impactful. And why activists can create their own endurance tests—sit-ins, extended vigils, hunger strikes—to show others what they are willing to do.

What‘s great about this framework is that it doesn‘t just make sense of how movements have an impact, but also gives some sense of what goals organizers might have in choosing different protest forms.

But when I tried to understand the movements I have worked with, I came to feel that other dimensions were important as well. As I’ve written: “But what if grassroots movements see themselves not just as claimants before the state, but as a rival power to it? What if they claim a bit of sovereignty for themselves? The mobilized communities described here do use their unity and numbers to illustrate their claim to represent the public as a whole. To create the shared impression that “everyone” is part of a mobilization, however, they also highlight diversity among themselves and carry out geographically expansive protests. And they demonstrate effective practical sovereignty over urban spaces and persistence in the face of state violence.”

These are, I think, four new dimensions. A mobilization that claims sovereignty has worth, unity, numbers, and commitment, but is also diverse, widespread, irrepressible, and in control. What do these four adjectives mean?

- Diverse: This includes and goes beyond the intersectional identities notion of diversity. Yes, it’s about including those oppressed, marginalized and excluded. It is those who were scorned claiming political voice. But also yes, it’s about joint action across lines of difference, showing people working together despite privilege and division. It is uniting to fight together. And yes again, it‘s about those sectors of society that have been pitted against each other finding common cause. It’s realized though unexpected juxtapositions: Teamsters and Turtles together at last, the office worker in a suit throwing back a tear-gas canister.

- Widespread: Movements demonstrate their political significance by being ubiquitous: We are everywhere. At the height of their water privatization protests, Cochabambans moved to erect road blockades on every street they could find. And in the United States, we’ve seen a move since at least Occupy in 2011 to maximizing the number of protest locations. This was definitely a feature of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, possibly the most widespread protest mobilization in American history. Here in 2025, No Kings seems to have doubled down on this strategy, meaning that many metropolises could boast multiple urban and suburban protests on the same day: as many as fifty separate locations in the San Francisco Bay Area. Much of the celebratory sharing that happened yesterday was geographical, with images from places like Boise, Salt Lake City, or Hattiesburg (Mississippi) treated as mic drop moments.

The last two elements of my list may just be at the horizon for the current protest wave in the USA, but they mark out where things could go as the protester–government standoff evolves.

- Irrepressible: When a movement surges back in to the streets after repression, it showcases the limits of state power. This feeling is definitely significant right now, with these protests surging both in places where police and military violence was displayed over the past ten days, and showing up in new places in outraged reaction. Anyone who has been on the streets when police have backed down, or gave up their hold on even a block of the city to allow protesters to surge in, knows the electricity that goes through a crowd that has lost its fear and disempowerment. Finding ways to protest through, or in spite of, physical attempts to prevent you from doing so is a powerful political statement.

- In control: Beyond that, lies the experience of protesters actually choosing what happens in the streets. Of public collective decisions on what happens next. This is why certain kinds of rallies and assemblies are uniquely empowering, because people choose on the spot what do, where to go, how to escalate, and whether to persist until their demands are one. The collective experience of direct action is its own unique form of self-empowerment.

The United States is a massive country with many cities, countless communities, and many, many places of gathering. It’s an exceptional challenge to walk forward through the different kinds of collective power sketched out here all at once. When face-to-face in one place we can get a sense of our potential, but we’ll need to find ways of keeping track of that across many settings.

Synthetic journalistic, movement media, and academic accounts can give us perspective, and I hope this outline of elements of power can help orient those accounts. Counting the number of locations, as being done by the Crowd Counting Consortium, is vital information. Yet summaries of crowd size and dispersion are useful, but also not enough. We need to thicken these accountings of where and how many with considerations of which alliances are emerging, which sectors of society are participating, and how daring and how contagious actions are. As well as what is working despite the kinds of force directed against it.

In the past, with thinner forms of communication and a greater reliance on centralized mass media, singular national protest gatherings may have been more important in building this shared sense of working together and achieving power. So did roving concentrated mobilizations, whether that was the trail from Birmingham to Freedom Rides to Selma to Chicago, or from Seattle to DC to Cancun to Miami. Now, in part because the adversary is more directly the national government, an Everything Everywhere strategy seems to be taking shape.