As we cheer on Egypt’s anti-regime uprising, we should also be learning as much as possible how it worked. Some things, of course, are only important in a society that has lived under decades of emergency rule. But most, I think, apply just about everywhere. Since we’ve seen government spying and storm trooper-style riot cops deployed in just about every country, it’s great when we can learn things that stop them.

Here are some of my favorites so far.

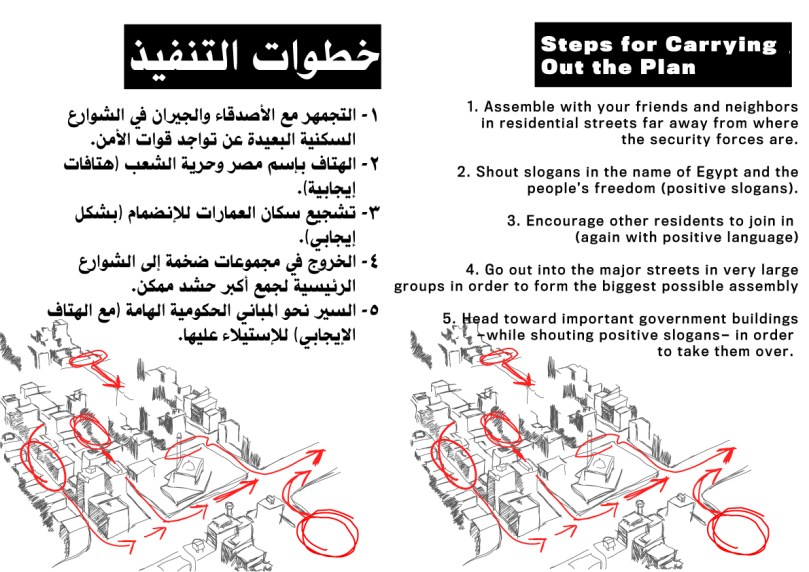

Open source protesting: Making its round in Egypt during the last days of January was a brilliant little pamphlet called “How to Protest Intelligently.” This easily reproducible, forwardable, xeroxable pamphlet brought together an open-ended set of tactics and strategies and widely distributed them. San Francisco bikers will be familiar with the well-distributed xeroxes that circulate at Critical Mass (some mockingly call this form of leadership “xerocracy”), but its relatively rare that protesters aim for mass distribution of their plans to the rest of society. When enough people are fed up, but might remain inactive without a plan, this can be strikingly effective.

By the way, open source is a metaphor here, that has relatively little to do with actual computers. It seems that e-mail and pdfs did actually help in Egypt, but mimeographs, printing presses, fax machines, or copiers would have functioned just as well in another era. (Non-blog-oriented hat-tip to the European collectives circulating open source windmill designs to put renewable energy into grassroots hands.)

You can read nine pages of the pamphlet at Indybay (the San Francisco Bay Independent Media Center), one of my favorite open media institutions.

Gather where you is, Converge on where you ain’t:* One piece of simple advice from the pamphlet is this universally applicable tactical plan. Apparently, it actually happened this way. Ahdaf Soueif, for example, reports:

This is the scene that took place in every district of every city in Egypt today. The one I saw: we started off as about 20 activists, after Friday prayers in a small mosque in the interior of the popular Cairo district of Imbaba. “The people – demand – the fall of this regime!” Again and again the call went out. We started to walk: “Your security. Your police –killed our brothers in Suez.”

The numbers grew. Every balcony was full of people: women smiling, waving, dangling babies to the tune of the chants: “Bread! Freedom! Social justice!” Old women called: “God give you victory.”

For more than an hour the protest wound through the narrow lanes. Kids ran alongside. A woman picking through garbage and loading scraps into plastic bags paused and raised her hand in a salute. By the time we wound on to a flyover to head for downtown we were easily 3,000 people. (“An eyewitness account of the Egypt protests,” Guardian, January 28)

* “If you can’t organize where you is, you can’t organize where you ain’t” — received Saul Alinsky-style wisdom

Missing step, How to Defend a Public Plaza from Cops and Mobs of Hired Thugs: Seriously, I’m curious. And a lot of experience has been generated.

How to make demands from a giant crowd: Now that Tahrir Square has proclaimed itself an “autonomous republic,” and demands are flying from every corner of Egyptian society, not to mention every foreign government, the crowds whose effort has made change possible are trying to articulate their demands. Here’s how:

In Tahrir, the square that has become the focal point for the nationwide struggle against Mubarak’s three-decade dictatorship, groups of protesters have been debating what their precise goals should be in the face of their president’s continuing refusal to stand down.

The Guardian has learned that delegates from these mini-gatherings then come together to discuss the prevailing mood, before potential demands are read out over the square’s makeshift speaker system. The adoption of each proposal is based on the proportion of cheers or boos it receives from the crowd at large.

Delegates have arrived in Tahrir from other parts of the country that have declared themselves liberated from Mubarak’s rule, including the major cities of Alexandria and Suez, and are also providing input into the decisions.

“When the government shut down the web, politics moved on to the street, and that’s where it has stayed,” said one youth involved in the process. “It’s impossible to construct a perfect decision-making mechanism in such a fast-moving environment, but this is as democratic as we can possibly be.” (“Cairo’s biggest protest yet demands Mubarak’s immediate departure,” Guardian, February 5)