It was an inescapable image of the 2025 presidential inauguration: the joint appearance of Mark Zuckerberg (CEO, Meta), Priscilla Chan (co-CEO and operating leader of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and Zuckerberg’s spouse), Jeff Bezos (founder, Amazon) Lauren Sanchez (Bezos’ fiancée and co-chair of the Bezos Earth Fund), Sundar Pichai (CEO, Alphabet/Google), Elon Musk (CEO, Tesla, SpaceX, and Twitter), Tim Cook (CEO, Apple), and Sam Altman (CEO, OpenAI). Upstaging governors and the incoming president’s cabinet, this roster of the giga-rich offered the blessing of the Silicon Valley to President Donald Trump and offered themselves as an on-stage symbol of what has been variously named the tech–industrial complex (by outgoing President Joe Biden), the Broligarchy (by Carole Cadwalladr among others), the attention economy (by Chris Hayes), and less recently surveillance capitalism (by Shoshana Zuboff).

If the inauguration served as something of a prom for tech oligarchs, it’s also a critical moment to think about how their power operates. It’s both quantitatively more extreme than prior rounds of monopoly capitalism, and tied to extraordinary ideas about future sources of wealth. As individuals, the founders and CEOs atop these corporate entities have way more power than even US corporate tradition usually provides.

The extraordinary personal concentration of dollars and power

First off, there’s a LOT of wealth in that one row: $653 billion among Chan, Zuckerberg, Bezos, and Musk

Google’s Pichai holds $1.3 billion, but he stands in the shadow of founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who have $266 billion together. The gap between Google founders Page and Brin, and current CEO Pichai highlight an staggering first-mover/founder advantage in many Silicon Valley firms, entrenching enormous wealth in early owners of these corporations. And these gaps are enabled by a corporate structure that provides founders with enormous voting power and disproportionate ownership of what eventually become large corporations.

Within the companies, they hold an extra level of voting power that exceeds even their share of the wealth.

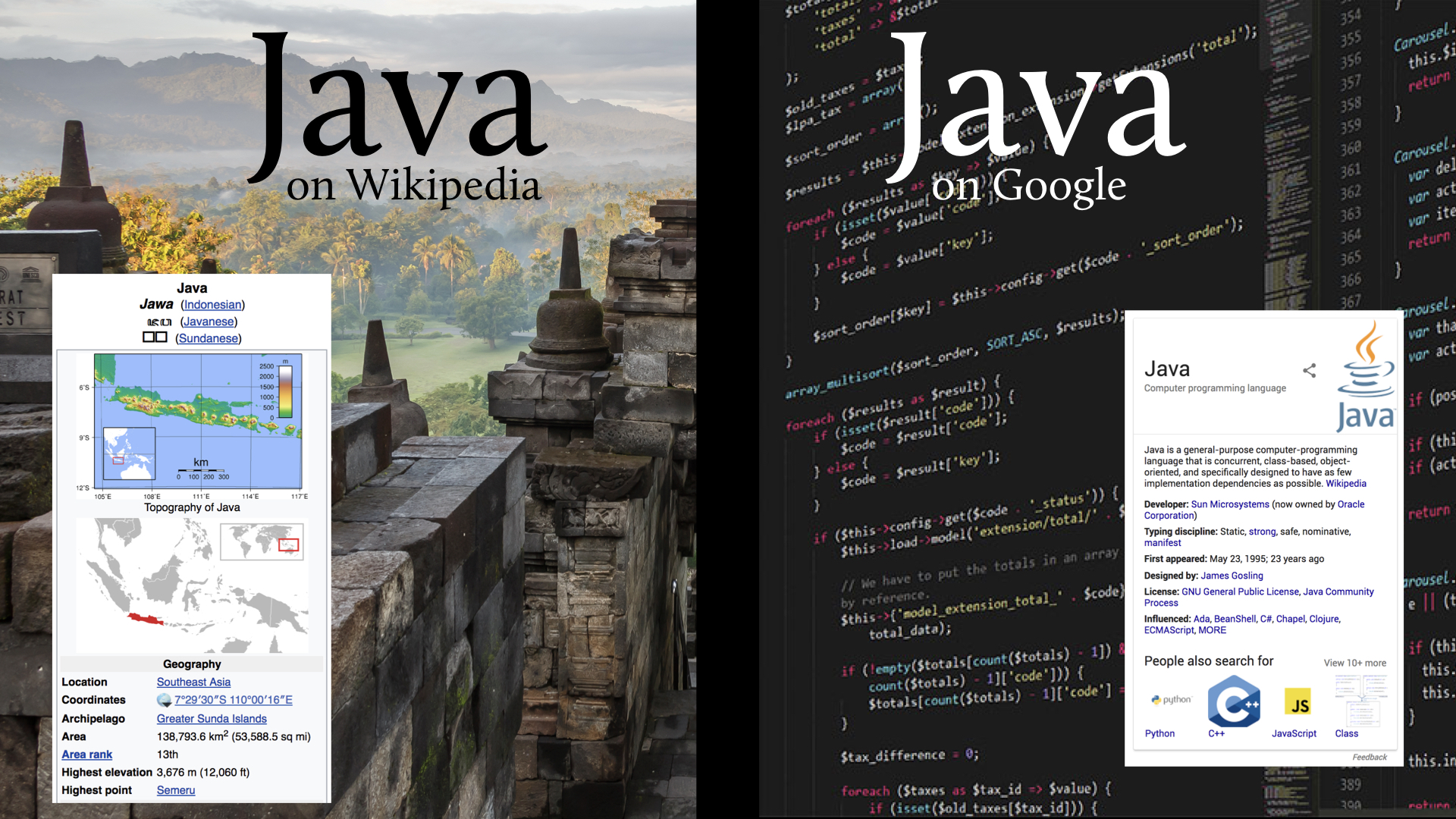

One way that Google’s founders institutionalized their freedom was through an unusual structure of corporate governance that gave them absolute control over their company. Page and Brin were the first to introduce a dual-class share structure to the tech sector with Google’s 2004 public offering. The two would control the super-class “B” voting stock, shares that each carried ten votes, as compared to the “A” class of shares, which each carried only one vote. …

This arrangement inoculated Page and Brin from market and investor pressures, as Page wrote in the “Founder’s Letter” issued with the IPO: “In the transition to public ownership, we have set up a corporate structure that will make it harder for outside parties to take over or influence Google.… The main effect of this structure is likely to leave our team, especially Sergey and me, with increasingly significant control over the company’s decisions and fate, as Google shares change hands.” (Zuboff, Surveillance Capitalism)

This makes actually-existing Google and Meta a lot closer in internal power dynamics to Elon Musk-owned Twitter than to Microsoft. Hence, this month’s turn-on-a-dime rejection of DEI and fact-checking by Mark Zuckerberg at Meta may reflect a kind of economic power unique to this sector, where founder-owners can exercise personal rule.

Outsized market values based on imagined future control

Despite the unusual internal structure, these are still publicly traded companies whose value is tied up in market expectations, and still massive employers whose functions depend on keeping their employees vaguely satisfied. In fact, tech firms with ties to the attention economy make up the majority the very largest companies by market capitalization—what shareholders estimate they are worth.

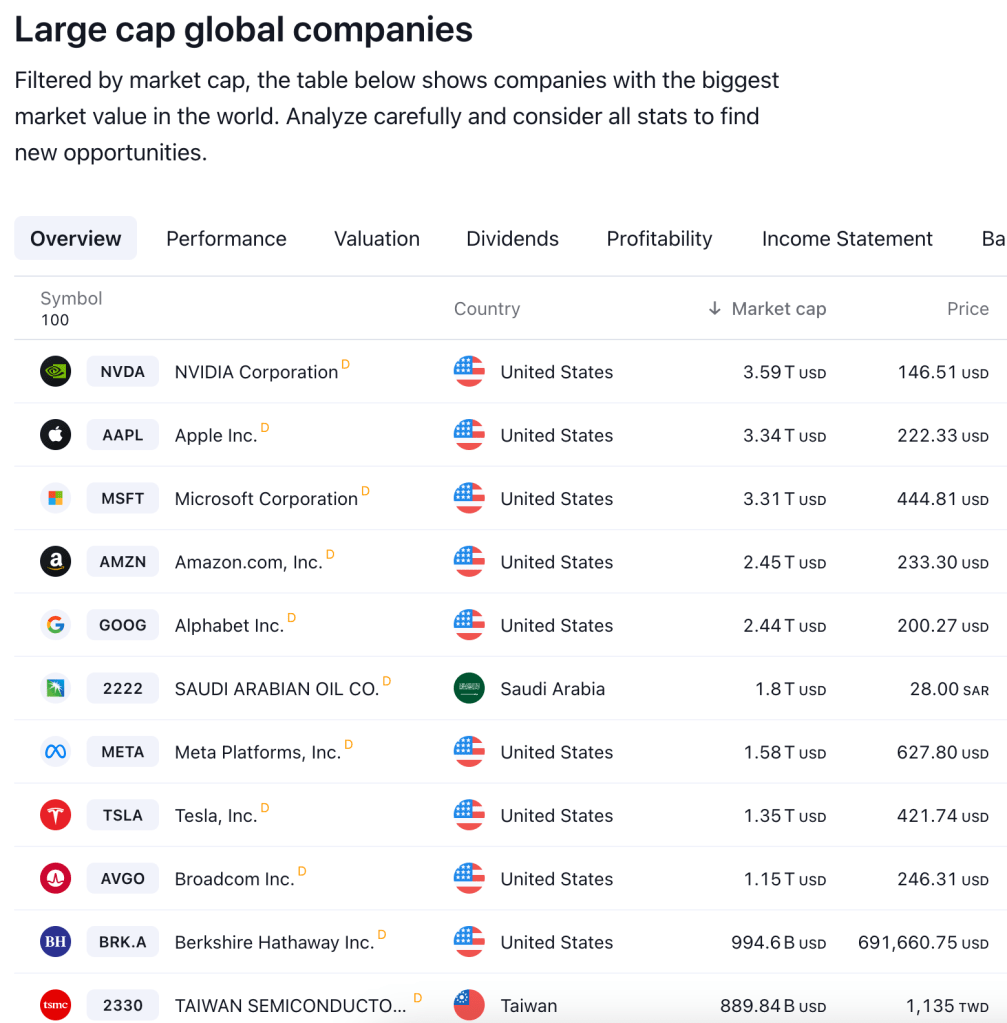

The five companies behind the presidential dais—Meta, Amazon, Alphabet/Google, Apple, and Tesla—weigh in at $11.16 trillion in market value. Adding in Microsoft (same sector, same inaugural donations, not on the dais) and NVIDIA and Broadcom (physical suppliers to this boom), we get a combined market capitalization of $19.21 trillion.

These corporations get a disproportionate amount of investor dollars, representing something approaching a quarter of the global stock equity market (estimated at $78 trillion in mid-2024). Needless to say they are a far smaller share of the global economy, whether measured in dollars of revenue or number of workers.

Collectively, stock markets imagine that these companies have not just their present revenue streams, but future control over larger and critical part of the global economy. Part of their monetary value is stories of future value, stories that may in part be fantastical. And their leaders’ personal wealth is heavily tied to just those stock market values: fundamentally they are fully invested in selling a narrative in which their products—advertising and marketing, behavioral prediction, digital infrastructure, and increasingly artificial intelligence will one day claim nearly all the value of the economy.

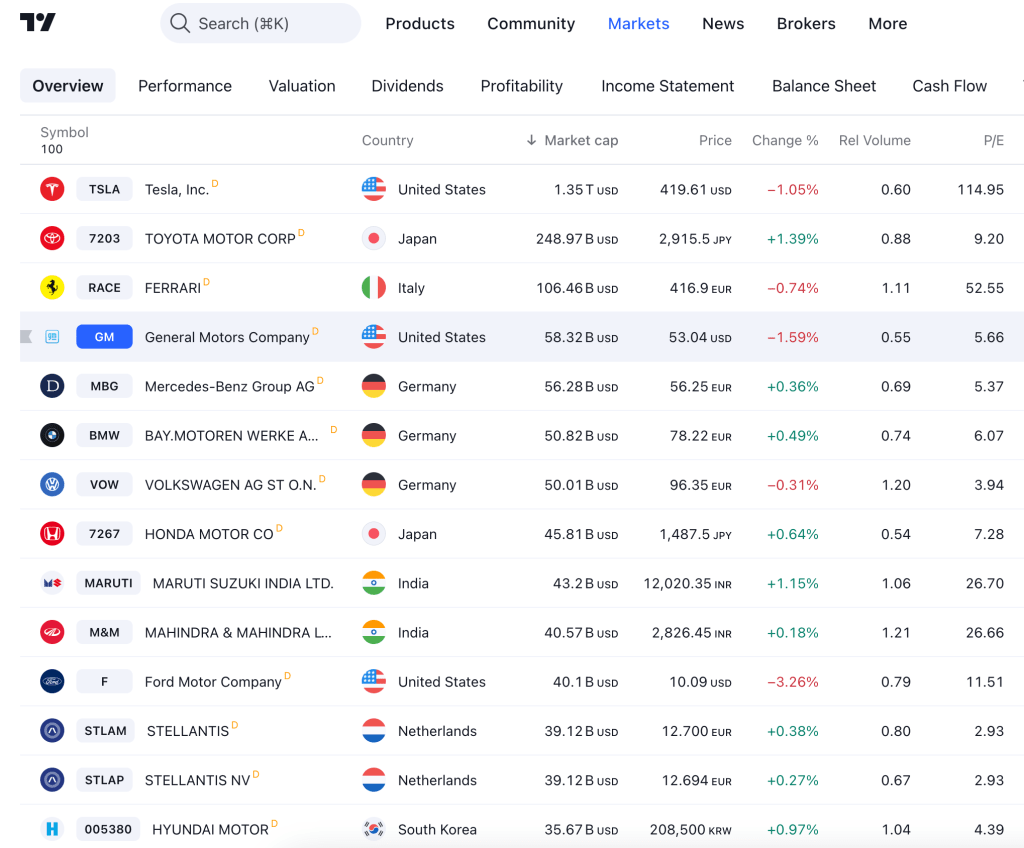

Tesla’s value in the stock market exceeds that of all other automakers put together, and is 114 times its earnings, while other carmakers (except Ferrari) run from 3x to 30x. Analysts estimate that over three-quarters of Tesla’s perceived value comes down to robotaxis and self-driving cars, technologies it has yet to deliver. Most of Musk’s wealth is from others’ bet that he has the secret key to the future.

So aside from the usual asks around taxes, subsidies, and freedom from regulation, these oligarchs will be seeking a way for the US government to sustain the illusions and collective future fantasies that amplify their wealth.