Bolivia is on the verge of a mild liberalization of its abortion laws after the Plurinational Legislative Assembly approved changes this week. On Wednesday, December 6, the Bolivian Senate approved a rewrite of the article of the country’s penal code that deals with abortion. While the code continues to treat abortion as a crime, and to threaten women who have them with one to three years in jail, it carves out new exceptions for some women who terminate their pregnancies within the first eight weeks of pregnancy. Women who are parents or caregivers to elderly or disabled members of their household, or who are students, may seek abortions without penalty. Perhaps more importantly, the revised law replaces a system that required pregnant women to seek judicial authorization for abortion with a simple form to be filled out within a medical setting. The simpler process will also be available under cases that were already permitted: abortion to protect the life or health of the mother, in the cases of rape, incest, or assisted reproduction without the woman’s consent; detection of fetal abnormalities that are fatal, and if the woman is a minor. The governing MAS-IPSP party backed the changes and President Evo Morales is expected sign them into law.

Bolivia’s current abortion law (es), enacted in 1973 under dictator Hugo Banzer, has been a public health disaster. Since it required authorization from a judge, and provided a very narrow set of circumstances to do so, it made seeking a legal abortion into a slow, uncertain, and costly process. In a recent two and half-year period, Bolivian hospitals recorded performing just 120 legal abortions, an average of fewer than 50 per year. Meanwhile, some 200 women seek clandestine abortions each day, according to a March 2017 Health Ministry estimate. Of these, around 115 seek follow-up care in hospitals for the side effects of abortion-inducing drugs or in recovery from clandestine surgeries. Over forty women died from the side effects of clandestine abortion in 2011, making unsafe abortion a major contributor to the country’s alarmingly high maternal mortality rate (National Study of Maternal Mortality (es), using 2011 data). Abortion led to 8% of all deaths of pregnant or post-partum women, and 13% of deaths under obstetric care.

The revisions to the law will not change the overarching framework surrounding abortion in Bolivia: criminalization. They do, however, acknowledge the ways that limiting family size and ending unwanted pregnancies can support women’s roles as caregivers and as students. These roles are the ones foregrounded by the Bolivian campaign group

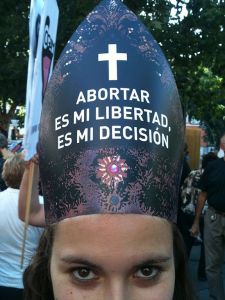

Bolivian feminists continue to demand that the state “Decriminalize my decision.”: “Our demand is the decriminalization! (It) is an… advance in the context of a conservative onslaught… we continue moving towards decriminalization.” (translation by Telesur)

https://twitter.com/monicanovillo/status/938408989934669824

For Elizabeth Salguero, former Minister of Cultures and prominent MAS-IPSP politician, the changes mark “a great step forward for sexual and reproductive rights.”

The yearlong debate on this bill has been marked by protest from the Catholic hierarchy and evangelical Christian groups who frame their opposition in terms of defending life. The Plataforma por la Vida y la Familia (Platform for Life and the Family) is calling on President Evo Morales to veto the legislation. However, the opposition campaign has been marred by impolitic outbursts from within its own ranks. As the Senate bill was being voted upon (eventually backed 23–9), opposition Senator Arturo Murillo shocked the audience by saying:

Kill yourselves. Let those women who say they want to do whatever they want with their bodies kill themselves. Do it, commit suicide, but don’t kill the life of another.

Mátense ustedes, mátense las mujeres que dicen que quieren hacer lo que les da la gana con su cuerpo, háganlo, suicídense, pero no maten una vida ajena

It was a phrase that stripped away all pretense of religious conviction, and the sanctity of human life, from his opposition to abortion. Yet Murillo’s apology “to those I offended” demanded “respect for my principles and my way of thinking about this sensitive topic.”

Senator Perez was not the first abortion opponent to be moved to a public outburst during this debate. Back in April, Jesuit priest and Radio Fides personality Eduardo Pérez Iribarne complained on the morning show Cafe de la Mañana that the president’s cabinet was unqualified to speak to family issues like abortion:

In the cabinet, I would like to ask who, besides [Vice President] Álvaro García Linera and his wife, lives with their family? Starting with Evo, [they are] divorce women and men, living separately, here and there. And this cabinet of people displaced for life is going to set the standard for how to have abortions?!

En el gabinete me gustaría preguntar, fuera de Álvaro García Linera y su esposa ¿qué miembros del gabinete tienen una convivencia familiar? Empezando de Evo, divorciadas, divorciados, separados, con aquí allá. Y ese gabinete de gente desplazada por la vida va a dar pautas sobre cómo hay que hacer los abortos.

If this weren’t enough, Father Pérez also piled on to Health Minister Ariana Campero (Wikipedia), a single woman who became the Bolivia’s younger cabinet member at age 28. Since then, she has endured cringe-inducing on-stage sexual harassment from a gubernatorial candidate and the Vice President, as well as a presidential admonition not to become a lesbian. On the same morning as his comments about divorcées in the cabinet Pérez effectively suggested that Campero was unqualified and had slept her way onto the cabinet:

Excuse me, miss, I don’t dare call her doctor, I don’t dare! It could be because I am gay man, but I don’t dare call her a doctor, I prefer to call her the Minister of Health. And why are you the Minister? I don’t know, I have been told rumors, but I don’t want to broadcast them because they are gossip.

¡Discúlpeme, señora, no me atrevo a llamarla médica, no me atrevo! Será porque soy un maricón, pero no me atrevo a llamarle médica, prefiero llamarla Ministra de Salud. ¿Por qué está de ministra? No sé, me han contado chismes, pero no quiero difundir porque son chismes.

Minister Campero responded in an op-ed: “Surely for you my six sins are being a woman, young, a doctor who studied medicine in Cuba, feminist, communist, and single; that is why you said what you said. Seguramente para usted mis seis pecados sean ser mujer, joven, médica graduada en Cuba, feminista, comunista y soltera; por ello dijo lo que dijo.”

Minister Campero responded in an op-ed: “Surely for you my six sins are being a woman, young, a doctor who studied medicine in Cuba, feminist, communist, and single; that is why you said what you said. Seguramente para usted mis seis pecados sean ser mujer, joven, médica graduada en Cuba, feminista, comunista y soltera; por ello dijo lo que dijo.”

The abortion debate has long revolved around the question of whether restrictions on abortion are born of concern for the sanctity of life, as one side claims, or about restricting the behavior of women who simply can’t be trusted. In this year’s Bolivian debate, the mildest steps to liberalize access to abortion have set off extreme attacks on women from abortion opponents, reinforcing the pro-choice claims that anti-abortion politics is rooted in misogyny.

Photos: Panel: National Pact for Depenalizing Abortion (Cambio newspaper). Abortion hat photo by Stéphane M. Grueso (El Perroflauta Digital).

[…] a year of drafting and debate, the significant but limited liberalization of Bolivia’s abortion laws lasted just six weeks. It was signed into law on December 15, 2017, as part of an omnibus reform of […]

LikeLike