Update: More on the Conisur communities and coca added, based on new reporting from Erbol; see below.

The long-promised counter-march from Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), this time in support of the Villa Tunari–San Ignacio de Moxos highway (Wikipedia) began last Tuesday, December 20. Around 300 initial marchers began the journey from Isinuta, on the edge of the park. Reinforced by hundreds more, the marchers should reach Cochabamba tomorrow, and expect to proceed onwards to La Paz. The countermarch is headed by the members of the Indigenous Council of the South (Consejo Indígena del Sur, or Conisur), a local organization of indigenous people inside TIPNIS, but living in the southernmost part of the the territory, entirely in the department of Cochabamba.

The march is understandably surrounded with controversy, and according to the opposition-leaning/center-right Los Tiempos, a lack of public enthusiasm. But rather than attempting to dismiss this countermarch, I write here to explain it.

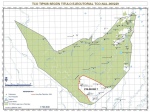

To understand this (counter)march, it is helpful to understand the organizational structure of TIPNIS indigenous peoples. The oldest and broadest organization in the territory is the Subcentral TIPNIS (indigenous organizations over large regions of the country are called Centrals and this is a smaller portion of a region). The Subcentral TIPNIS was founded in 1988 and received the land title to TIPNIS from Evo Morales in 2009. It pertains to the Central de Pueblos Étnicos Mojeños del Beni. The Subcentral Securé includes nearly all communities on the Securé river itself, and belongs to the Consejo de Pueblos Indígenas del Beni.

Conisur includes most but not all communities in the southernmost part of the territory. The Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCA) database estimates Conisur’s population at 915 people and lists 14 Conisur communities: Limo del Isiboro, Santa Fe, San Juan del Isiboro, San Juan de Dios, San Benito, Sanandita, Secejsama, Fátima, San Antonio, Mercedes de Lojojota, San Juan de la Angosta, Carmen Nueva Esperanza, San Jorgito, and Puerto Pancho. Conisur affilialtes with the Coordinadora de los Pueblos del Trópico de Cochabamba (CPITCO); [La Razón reports 20 communities]. By comparison, estimates for the indigenous population of TIPNIS as a whole are around 12,500 in 64 communities. CPITCO’s website acknowledges, “CONISUR is an organization basically created and supported by the Cochabamba Prefecture, which serves it as a mechanism for channeling aid to the communities of the south and through this to defend its sovereignty over the area. [CONISUR es una organización básicamente creado y apoyado por la Prefectura de Cochabamba a la cual le sirve como mecanismo para canalizar ayuda a las comunidades del sur y de este modo defender su soberanía sobre el área.]” (The Prefecture—now the Gobernaciónor Governorate—is especially interested because the Cochabamba-Beni border inside TIPNIS is not officially demarcated.)

The communities in Conisur are principally located inside Polygon 7, the region around Isinuta which been colonized since 1970 by outside settlers, principally coca growers. The Polygon is separated from TIPNIS by the Linea Roja (Red Line) which is meant to prevent the advance of further settlement into the park, but in practice has repeatedly been moved to allow just such settlement. Bolivia’s Fundación Tierra estimates that some 20,000 agricultural settlers live in the 100,000-hectare Polygon 7, swamping the local indigenous population whose territory they have largely deforested.

All three of the parent organizations of the TIPNIS indigenous organizations are members of CIDOB. And all three organizations joined in the May 2010 meeting of indigenous residents condemning the Villa Tunari–San Ignacio de Moxos highway. However, political opportunities, local relationships with cocaleros, and divergent economic needs have driven Conisur apart from the residents in the rest of the Isiboro Securé National Park and Indigenous Territory.

Politically, as regular readers of this blog are well aware, the highway has become a major priority of the MAS-IPSP party. MAS-IPSP has controlled the departmental government since the 2008 revocation referendum. The party began its meteoric rise in eastern Cochabamba specifically the Chapare province whose capital is Villa Tunari. Governor Edmundo Novillo has made no secret of his support for the highway, and he plays a key role in its promotion committee. Since June, numerous MAS officials including Novillo, President Evo Morales, and Vice President Álvaro García Linera have been frequent visitors to the Conisur-aligned area of TIPNIS. They’re visits have served to rally support for the highway and to put an indigenous face on a project that is being pursued in contravention of the principle of indigenous consultation.

Four decades of cocalero settlement have created a variety of relations between them and the indigenous inhabitants of Polygon 7. Fundación Tierra documents intermarriage and indigenous participation in the coca growers’ unions’ standard-sized plots for growing coca. However, according to press visits (like this one by La Razón), relations are not equitable. Instead, indigenous people are often dependent, landless laborers in their own land, earning around 20 Bolivianos (a bit less than US$3) to harvest a coca plot or selling their fish or wild meat to colonists for around 300 Bolivianos (~US$40) a month. Some told the newspaper the cocaleros prevent them from joining in coca planting. Others earn income by authorizing the cutting of timber, and the elimination of the forest on which their lives once depended.

Unlike those living in the intact sections of the park, the indigenous in the colonized areas have already moved from a way of living interdependent with the ecosystems of the park to one that is integrated with the national economy. Right now, they are living at the bottom of the heap in the cash economy, relying on income from the growers of the regions’ key cash crop. This goes a long way to explain why they see a shared economic interest with the coca growers in the road. They also could see both educational and economic benefits from the expansion of formal schooling in their communities. While schools do not have to follow the roads, in practice the Conisur communities are being registered for schools right now. With this registration comes the Juancito Pinto school attendance bonus, 200 Bs paid to parents per student. This new payment may have furthered aligned their interests with the departmental government and thereby the road.

Added, 2 Jan: Further reporting on indigenous coca planting comes from the Cochabamba center-left daily Opinión and the community radio network Erbol. Opinión describes three levels of involvement by indigenous residents: labor in colonists’ coca harvesting, small-scale unofficial coca planting, and membership in coca growers’ unions. Coca is a good cash crop option for those who are enmeshed in the cash economy, but disconnected from the road network: the light coca leaves can be dried, packed up, and carried to larger settlements for sale. However, only union members can sell their leaves in large, official markets, which are controlled by the union federations. Opinión profiled in particular the community of San Antonio as a coca-growing Yuracaré indigenous community. Erbol has now published quotes from an interview “four months ago” with Conisur leader Gumercindo Pradel, confirming that “five to seven” Conisur communities grow coca: “There are five to seven communities that are dedicated to planting coca and which are affiliated with the Federation of the Tropic [one of the Six Federations of cocaleros]. [Son cinco a siete comunidades que se dedican a la siembra de la coca y que están afiliadas a la Federación del Trópico.]” Since the march began, however, Pradel has insisted that Conisur communities are not coca cultivators. // end update //

Across the world, indigenous rights struggles over development projects often see the fostering or exacerbating of internal divisions by those actors who promote the project. This makes the current counter-mobilization in TIPNIS familiar, even if few expected such a divisive move from the indigenous-identified government of Evo Morales. International and Bolivian standards around free, prior, and informed consent by indigenous have a provision to avoid this problem: an insistence that the pre-existing and recognized structures of governance be the basis of indigenous consultation. While the schismatic history of TIPNIS indigenous organizations complicates this picture, the Morales government clearly recognized the Subcentral TIPNIS as the local authority over the National Park and Indigenous Territory. By changing course when the Subcentral spoke out against its highway project, the MAS government is following in the footsteps of the divide-and-conquer strategies by governments and corporations it once condemned.

[…] The long-promised counter-march from Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), this time in support of the Villa Tunari–San Ignacio de Moxos highway (wikipedia) began last Tuesday, December 20. Around 300 initial marchers began the journey from Isinuta, on the edge of the park. Reinforced by hundreds more, the marchers should reach Cochabamba tomorrow, and expect to proceed onwards to La Paz. The countermarch is headed by the members of the Indigenous Council of the South (Consejo Indígena del Sur, or Conisur), a local organization of indigenous people inside TIPNIS, but living in the southernmost part of the the territory, entirely in the department of Cochabamba. | The march is understandably surrounded with controversy, and according to the opposition-leaning/center-right Los Tiempos, a lack of public enthusiasm. But rather than attempting to dismiss this countermarch, I write here to explain it. Read more here […]

LikeLike

[…] the consultation, and they reacted with outrage to the agreement’s announcement. Meanwhile, CONISUR, a separate organization in the region that represents indigenous communities overrun and now […]

LikeLike